In this guide

Hide menu4. Education and norm change

Show sections4. Education and norm change

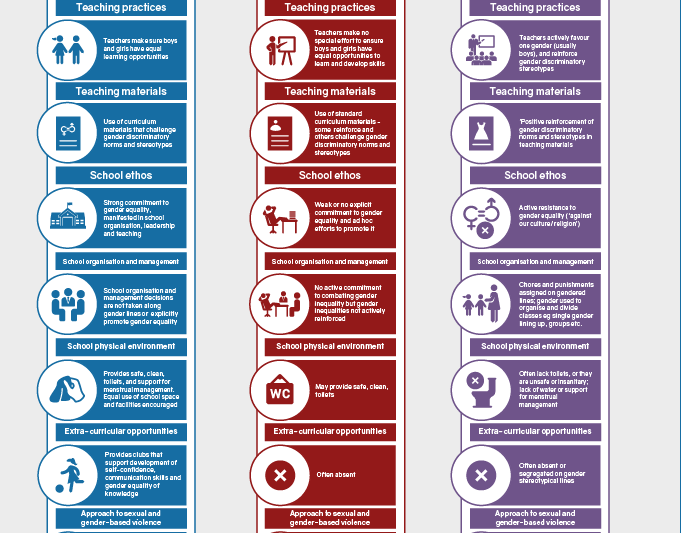

This interactive diagram shows stylised routes to 1) change in a ‘standard’ school, 2) in a school that accelerates change by paying specific attention to promoting gender equality, and 3) in one where the positive potential of education to promote norm change is disrupted.

Few studies examine the impact of girls’ education on changes in community level norms specifically, but a significant body of evidence records shifts in knowledge, self-confidence, attitudes and practices – the building blocks of norm change. Examples include the World Bank’s On Norms and Agency by Muñoz Boudet et al. (2013), which draws on primary research in 20 countries to highlight education as a key driver of shifting gender norms (or of norms becoming less strict). Studies focused on particular issues (such as UNICEF’s 2013 Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting: A Statistical Overview) also highlight how education contributes to changing norms and practices. There is also a growing body of evidence about the ways in which schooling can become more gender-sensitive and play a greater role in promoting gender equality, which we summarise here.

How does education lead to change in gender norms?

A growing body of evidence suggests that the following are key mechanisms:

Developing self-confidence and communication skills

The self-confidence to challenge discriminatory norms and practices and overcome setbacks, and the communication skills to speak out and share your views are two building blocks for norm change. According to Kautz et al. (2014) they are also increasingly seen as vital for economic well-being and effective participation in society. Marcus and Page (2016) discuss evidence on how education can enhance self-esteem and resilience among adolescent girls. There are surprisingly few retrospective studies with women looking back on how their education has (or has not) helped them develop these and other skills. Studies from Tanzania by Willemsen and Dejaeghere (2015) and Posti-Ahokas and Hanna (2013) explore girls’ views about how education has contributed to their self-efficacy, enabling them to be confident, resourceful and knowledgeable individuals who can handle setbacks.

If more girls enter the labour market and other public spheres with greater self-confidence and stronger communication skills they may create their own virtuous cycle, challenging stereotypes about the relative competence of men and women, as well as pervasive views on gender roles. However, few studies explore these processes in detail; the links remain theoretical or are backed up by only a handful of in-depth qualitative studies rather than a significant body of evidence.

Exposure to new ideas about gender within schools

One obvious route for change is exposure to new information and ideas that challenge established gender norms. A significant body of literature explores the effects of sexuality education on young people’s factual knowledge and their ideas about gender equality.

UNESCO’s (2015) review of Comprehensive Sexuality Education found that ‘issues of gender and rights are almost consistently absent or inadequately covered through current curricula across all regions.’ It appears that – in mainstream school curricula – shifts in young people’s thinking on gender norms and practices are driven largely by new information (often in science classes on health or biology or through education on personal and social relationships) rather than education that questions discriminatory ideas and norms explicitly. ODI’s qualitative research among the Hmong ethnic minority in northern Viet Nam confirms this: young people reported that health information they learnt in school changed their ideas about the ideal age of marriage (Jones et al., 2014).

‘My wife is 21. I think that if I married a younger girl with an underdeveloped body, my baby would be malnourished, unable to grow and slow to develop. I learnt it when I was in school.’

(Young man in focus group discussion)

‘If she gets married at the age of 20, she will not be as poor and she will give birth more comfortably.’

(24-year-old mother)

Levtov (2014) summarises attempts to integrate material on gender equality more widely across school curricula – in social studies, personal, health and social education, and within other subjects (e.g. as a topic for argument or debate in language classes). However, the impact on gender attitudes and norms among young people has not yet been evaluated.

Co-education

Qualitative evidence suggests that social interaction between boys and girls and co-education can lead young people to challenge gender stereotypes. For example, Alice Evans’s 2014 qualitative study in Kitwe, Zambia, found that co-education had led children to reject stereotypes of boys and men as being more intelligent. This reflected boys’ experience over time of seeing girls in their classes who mastered their subjects more quickly than some of their male peers. Co-education also reduced the extent to which boys and girls saw each other exclusively in sexualised terms – a change carried forward into their working lives. Girls from co-educational high schools reported that they learned to stand up for themselves and to deal with male-dominated workplaces.

Similarly, a study by Arnot et al. (2012) found new patterns of communication and gender relations being established at co-educational schools in northern Ghana. At junior high-school level, relationships between boys and girls were mostly platonic and academic, with students helping each other with assignments and class work based on academic ability rather than gender, though these relationships became more sexualised after puberty.

There has been much debate about the relative benefits of mixed-sex and single-sex schooling for girls’ self-confidence and empowerment, and learning outcomes for both girls and boys. Yet the evidence is conflicting. The 2014 study by Unterhalter et al. on interventions to promote gender equality found no clear evidence to support single-sex schooling, as quantitative studies often fail to take the elite or selective nature of many single-sex schools into account. Levtov’s 2013 analysis of the literature suggests that teacher attitudes and active commitment to gender equality matter more than whether students are educated in single-sex or mixed-sex groups.

Role models

Role models – such as teachers, classroom assistants, mentors, counsellors and visiting speakers – can also raise girls’ aspirations by demonstrating that educated women can work in a variety of careers. Similarly, male teachers who display gender-equitable attitudes can be powerful role models to boys. Surprisingly few studies have examined how this contributes to shifts in gender norms, although Marcus and Page (2016) summarise evidence on the impact of mentors, counsellors and classroom assistants, such as the Learner Guides supported by the Campaign for Female Education (Camfed). Most evidence outlined the impact on girls’ academic achievement; only one study (Dejaeghere et al., 2015) highlighted the impact of a school counsellor as a role model.

Normalisation of school attendance

Large numbers of girls attending school and moving around in this public space can help to shift norms on female mobility, the acceptability of education, and gender equality more broadly. Alongside communications from government or non-governmental organisations (NGOs) on the importance of girls’ education (a common approach in many countries), this can start to shift norms so that girls’ education is seen as valuable and a responsible course of action for parents. Schuler’s 2007 qualitative study in rural Bangladesh shows the power of change among reference groups of girls’ fathers in driving norm change on girls’ education. Other factors included stipends to reduce the financial costs of girls’ education to families.

Changing community-level perceptions of girls and young women

The value attached to education by the wider community affect the perceptions of girls and young women who have attended school. Lloyd and Young (2009) found that girls who attend school are often seen by other community members as knowledgeable and more worthy of respect. Studying northern Ghana and India, Arnot et al. (2012) suggest a shift in perceptions of young women who have attended school among their partners/ spouses and in-laws. This, in turn, contributes to subtle changes, such as more joint activities between husbands and wives, and (in India) slightly less control over young wives by mothers in-law. Women who had been to secondary school, in particular, were also more able to influence household decisions.

Gaining such respect is particularly important for girls from poor backgrounds, ethnic minorities and other marginalised and disadvantaged groups, not just in improving gender relations but also enabling them to chart their life course on more equal terms (see Crivello, 2009 and Schuler, 2007).

Maximising the potential of education to change gender norms

Schools with an explicit commitment to gender equality can accelerate changes in gender norms by instituting new, gender-egalitarian practices. These include the following:

Changing the school environment

A growing body of literature highlights the importance of a gender-equitable school environment for gender norm change, as highlighted by Marcus and Page (2016). As well as gender-equitable curriculum content, teachers’ practices within the classroom and the wider organisation of the school can foster principles of gender equality that, in turn, challenge assumptions about the ‘naturalness’ of gender roles.

Levtov’s 2014 overview of the impact of initiatives to promote gender-equitable values and practices among teachers ( ‘gender-responsive’ education) finds that they have generally improved learning outcomes and helped to promote more gender-equitable attitudes among students. The Forum for African Women Educationalists (FAWE) has, undertaken a major training programme on ‘gender-responsive pedagogy’ for two decades. A study of its impact concluded that it has helped teachers treat boys and girls more equally: they call on girls and boys to answer questions, challenge all learners more, and set up group work so that girls and boys learn from one another. Institutionalising gender-responsive teaching requires a long-term commitment to challenge both teachers’ own gender stereotypes and norms among teachers about effective teaching methods, as Nabbuye’s 2018 study of Uganda demonstrates.

A strong gender focus in curricula

Efforts to promote more equitable gender norms have moved from their community base to mainstream education, sometimes as part of personal, health, social and relationships education, and sometimes as stand-alone initiatives delivered by external facilitators working with schools. The best-known is the Gender Equity Movement in Schools (GEMS) programme (see case study), which started in India and has now spread to Bangladesh, the Philippines and Viet Nam, among other countries.

Studies by Erin Murphy-Graham suggest that gender equality education is far more effective when embedded in a broader education programme that helps people develop critical thinking and citizenship, as well as mastering knowledge and core academic skills. Murphy-Graham’s 2009 study found that participants in the Sistema de Aprendizaje Tutorial (SAT) approach to education (see case study) had used their learning to negotiate more gender-equitable practices at home, and had the skills to turn aspirations into reality, challenging norms about appropriate occupations for women.

Addressing gender bias in textbooks

Gender bias in school textbooks and educational materials is under-researched; as Blumberg (2008) explains, this problem is understandably seen as less urgent than enabling millions of out-of-school children to go to school or improving the quality of their schooling. However, Blumberg’s detailed analysis shows how gender stereotypes in textbooks can help to cement discriminatory gender norms, and discusses efforts to revise learning materials to promote gender equality. The 2004 study by Mensch et al. (subscription required) on education and gender norm change among Egyptian adolescents reaches similar conclusions.

Tackling sexual and gender-based violence in schools

Sexual and gender-based violence in schools is increasingly recognised as a deterrent to enrolment, a major cause of school drop out and a negative influence on educational outcomes, particularly for girls but also for boys. Such violence in and around schools reflects and reinforces wider norms about the acceptability of sexual harassment, around heterosexuality as normative, and about consent and power in gendered and sexual relationships. Work by Parkes et al. at the Institute of Education at University College London, supported by UNGEI, has developed a useful conceptual framework for understanding different dimensions of this issue. It has brought together data on the scale of the problem, and provides pointers about how to eliminate gender-based violence, including homophobic violence, in and around schools.

Girls’ clubs and gender equality clubs in schools

Extra-curricular activities, such as girls’ only or mixed-sex clubs promoting gender equality, can challenge discriminatory norms and practices, and sometimes norms related to powerful taboos. Typically school-based, these clubs have multiple objectives: to enhance girls’ self-confidence and communication skills, to educate them about gender equality and their legal rights and, in some cases, to improve their educational outcomes through study support. Contributing to transforming gender norms is generally an indirect objective. However, there is quantitative evidence of the impact of such clubs on attitudes to gender equality, which may indicate changing norms, as in the Taaron Ki Toli and GEMS programmes in India. According to the study by Jones et al. (2015) on Ethiopia, there is also qualitative evidence of girls (and boys) learning new information and changing attitudes to gender equality as a result of participating in school clubs. This is borne out by other studies from the Overseas Development Institute (ODI) by Bantebya et al. (2015) on Uganda and Jones et al. (2015) on Viet Nam.

‘The school-based activities give us information about how we should not be ashamed of menstruation and should not let it stop us from going to school; we should not get married early because this will stop short our education; and that we should share household chores so that we both have time to study.’

(14-year-old girl from a Straight Talk Foundation club, Uganda)

For more, see ALIGN’s guide on girls’ clubs, and Marcus et al. (2017) on the impact of girls’ clubs and life skills programmes.

Transforming masculinities through education

There is a strong association between education, particularly secondary education, and changing masculinities. Barker et al. (2012) suggest key ways in which secondary education contributes to more equitable gender norms:

- Secondary class sizes are usually smaller, which reduces teacher stress and may be more conducive to building the critical thinking associated with justice-based reasoning and more gender-equitable attitudes.

- Boys who reach secondary school generally have more interaction with girls as equals in the classroom over longer periods. The enforcement of rules and collective solutions to problems may contribute to a greater awareness and practical experience of social justice, spilling over into notions of gender equality.

- Secondary school teachers often have higher levels of education themselves, making it more likely that they will promote and support gender equality.

The impact of schooling on masculinities may vary. For example, none of the men in the Promundo and ICRW study of Men Who Care identified their education as a key factor in their adoption of non-traditional gender roles – in this case, professional caring roles or providing most of the care for their own children. This contrasts with the findings on general attitudes to gender equality, and on issues such as gender-based violence, son preference and child marriage.

As boys and men have become increasingly recognised as potential change agents, there have been more attempts to promote gender-equitable masculinities through formal and informal education. Look out for ALIGN’s guide on masculinities and gender norms in 2019.

The risks of backlash

Efforts to promote gender equality frequently lead to backlash. There appears to be limited evidence of backlash related to the promotion of gender equality in school settings (there is more evidence concerning informal education).

Policy question: Does gender equitable education improve learning outcomes?

The rigorous review of school environments and girls’ learning and empowerment by Marcus and Page (2016) brings together evidence on this question. While there are few comparative studies with control groups, evaluations of projects that promote gender-egalitarian learning environments suggest that they help to improve learning outcomes for girls and boys alike. Evaluations of Transforming Education for Girls in Nigeria and Tanzania (TEGINT), Camfed’s Learner Guide programme in Tanzania and Zimbabwe, and Plan’s Building Skills for Life programme found evidence of improved exam pass rates in participating schools. Qualitative evidence of the gender-responsive pedagogy approach pioneered by the Forum for African Women Educationalists (FAWE) also shows greater engagement in learning among girls and boys.

Sources: Marcus and Page (2016); Mascarenhas (2012); Para-Mallam (2012); Camfed website.