- Blog

- 2 April 2024

From ‘witches’ to powerful agents of change: the critical role of grandmothers

- Author: Judi Aubel

- Published by: ALIGN

Programmes that aim to shift harmful gender-based social norms that affect adolescent girls frequently target girls. Sometimes they also target parents, and, increasingly men and boys. But grandmothers and other older women are rarely involved. These programmes often focus on the need for an enabling environment around girls to support changes in social norms that affect their education, marriage and the practice of female genital mutilation/cutting (FGM/C). However, grandmothers are often completely overlooked in these conversations.

Why is this?

The causes of their exclusion may include: limited understanding of the multi-generational family systems that prevail in non-western societies; ageist attitudes and perceptions of grandmothers as barriers, as conservative and resistant to change; and linear models of change that do not consider the whole family systems in which girls are embedded. Yet in societies that are structured around a family hierarchy, elders have authority and can influence the development of girls and younger women, in particular.

In years past, Grandmother Project – Change through Culture (GMP) documented the positive effects of grandmother involvement in maternal and child health programmes in Senegal, Mali, and Sierra Leone that all demonstrated grandmothers’ ability to learn and to change. In southern Senegal, we hoped that involving grandmothers would help to shift deep-seated cultural norms around girls’ education, child marriage, teen pregnancy and FGM/C as part of our Girls’ Holistic Development (GHD) programme. We believed that involving these guardians of tradition was vital to drive sustained change in these norms. However, we suspected that persuading grandmothers to abandon traditional norms related to these aspects of GHD might be more difficult than shifting norms around maternal and child health, such as breastfeeding practices. We were not sure that they would be open to change.

A grandmother-inclusive strategy to promote change

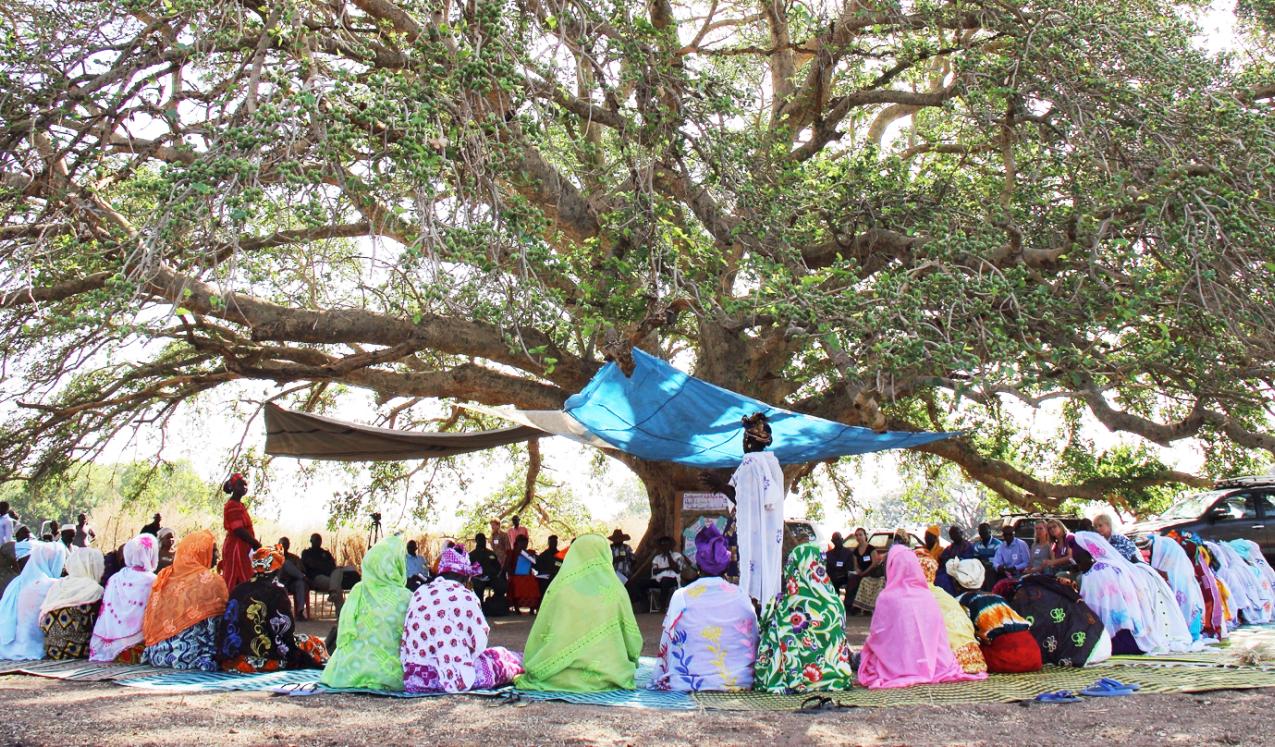

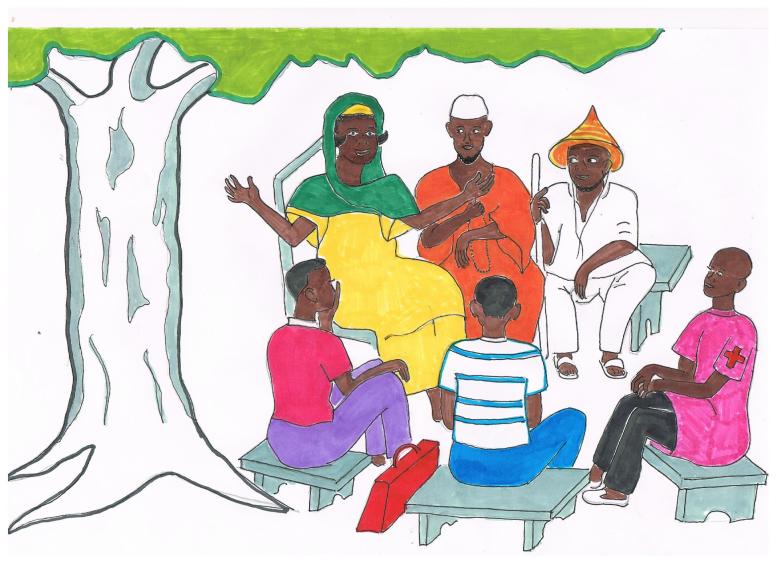

Our strategy to promote community-wide support for GHD targets community actors who can either block or facilitate change, namely, men and women of three generations (elders, adults and adolescents), traditional and religious leaders, teachers and community health workers. An initial listening study in local Peuhl communities revealed the central role of grandmothers in every aspect of a girls’ upbringing. The grandmothers interviewed expressed their regrets that other programmes had not involved them.

At the same time, they also lamented that mothers of young children sometimes discourage them from spending time with grandmothers, accusing them of being ‘witches’. Such accusations reflect the tension that often exists between mothers-in-law and daughers-in-law and is a way for young mothers to vent their hostility toward oppressive mothers-in-law.

Given grandmothers’ involvement in all aspects of the lives of women and children, and their influence on men’s attitudes and decision-making, the GHD programme sees grandmothers as a vital social resource for change – as an asset. Their inclusion aims to strengthen their knowledge of adolescence and enhance their individual and collective empowerment to promote change for girls. Key activities include: grandmothers as story-tellers in schools; Days of Praise of Grandmothers; Leadership training of grandmothers; and the creation of Community Alliances of Grandmothers, Girls and Mothers to strengthen intergenerational relationships for the collective promotion of GHD. As well as recognising their role and experience, the programme challenges grandmothers to reflect on some harmful traditions, including FGM/C and child marriage.

From ‘witches’ to powerful agents of change

An evaluation of GHD in 2019/2020 concluded that the intergenerational and grandmother-inclusive approach has contributed to changing social norms around girl’s education, child marriage, teen pregnancy and FGM/C. The evaluation, conducted by the Institute of Reproductive Health (IRH), Georgetown University, in collaboration with Professor Mohamadou Sall of Cheikh Anta Diop University, Dakar, identified the involvement of grandmothers as a key factor in those changes, noting that the GHD programme ‘empowers grandmothers to act collectively to promote and protect girls’.

The intergenerational approach and the involvement of both males and females have spurred dialogue that has helped to build a consensus for change. The involvement of grandmothers and the reaffirmation of their traditional role in communities have been found to give them the confidence to revisit old practices and to embrace new ones.

The evaluation has revealed a significant transformation in grandmothers’ roles and attitudes. One grandmother, Salimata, said:

‘Before we were called witches. Now our role is recognised, and we are using our influence to improve the well-being of children, especially girls’.

While grandmother Binta explained:

‘Now we spend time with girls and discuss many things including their studies, sexuality and putting off marriage’.

Adolescents appreciated this shift in attitudes: Khady, for example, stated that:

‘Thanks to the grandmothers, we have not yet been married off. They were able to convince our parents to wait’.

And a village headman commented on the influence of the local grandmothers, saying:

‘FGM has been abandoned here thanks to the grandmothers. When the grandmothers decided to stop the practice, no men could oppose their decision’.

The research shows that grandmothers in communities that have taken part in this programme are now much more involved than grandmothers in other communities when it comes to family decisions about girls’ education (87% vs 19%, respectively) and marriage (77% vs 30%). Surprisingly, the guardians of tradition have become confident agents of change for GHD.

According to the evaluation team, Peuhl communities are known for their tenacious attachment to their culture and the evaluation report states that ‘grandmothers are generally the most fervent defenders of tradition’. Professor Sall asserts that communities often reject programmes that aim to change social norms if they ignore the socio-cultural context, including the role and influence of elders.

So how does he explain the transformation of grandmothers from disparaged and ignored ‘witches’ to social change agents? As a Peuhl himself, he understands the authority of grandmothers in the lives of women and girls. He contends that if grandmothers are ‘to use their influence and power for the wellbeing of girls, they need to be recognised, valued and given social legitimacy.'

Professor Sall commends GHD for recognising the importance of grandmothers’ role with their granddaughters and for bolstering their collective sense of responsibility to all girls in their communities. He concludes that GHD demonstrates that ‘grandmothers represent a cultural lever for changing social norms.’

© Grandmother project

Involving grandmothers to shift gender norms: lessons for the future

- Ageist western attitudes in many development organisations overlook, and sometimes disparage the role and influence of older women in relation to the lives of younger women and girls.

- Driving community-wide change in gender-based attitudes and norms requires the involvement of not only those who are victims of those norms, but also key community actors across three generations: adolescents, parents and elders.

- Gender-based norms are rooted in culture. Sustained change in the harmful norms that affect girls requires the involvement of those who perpetuate such norms, namely the guardians of tradition, i.e. the elders of both sexes.

- Strengthening communication and creating alliances between girls, mothers and grandmothers can build a powerful force for positive change in harmful gender-based attitudes and practices.

- Changing grandmothers’ attitudes and practices requires an approach based on respect, listening and dialogue. Experienced grandmothers are not receptive to approaches that tell them what to do.

About the author

Judi Aubel is a social scientist-development practitioner. She holds a PhD in Anthropology and Education (University of Bristol), a Masters in Public Health (UNC) and a Masters in Adult Education (ASU). She has worked the past 30 years in research and development of culturally-grounded interventions to promote maternal, child and adolescent health in Africa, Asia and Latin America. She is the co-founder and Executive Director of an American and Senegalese NGO, Grandmother Project–Change through Culture (GMP) established in 2005.

- Countries / Regions:

- Mali, Sierra Leone, Senegal

Related resources

Briefing paper

5 November 2025

Published by: ODI Global, ALIGN

Journal article

26 July 2024

Published by: PLOS one

Report

8 May 2024

Published by: UNICEF

Report

22 February 2024

Published by: ODI Global

Toolkit

16 May 2023

Published by: Girls Not Brides

Report

3 March 2023

Published by: ODI Global

Briefing paper

8 February 2023

Published by: Girls Not Brides

Briefing paper

1 November 2022

Published by: Care, Tipping Point

Briefing paper

1 October 2022

Published by: UNICEF

Briefing paper

6 April 2022

Published by: Girls Not Brides

Briefing paper

31 January 2022

Published by: Girls Not Brides

Case study

1 January 2022

Published by: Care