- Blog

- 1 December 2022

Unpacking the context of femicide in Mexico

- Author: Diana Jiménez Thomas Rodriguez

- Published by: ALIGN

In the 1990s, the city of Ciudad Juárez on the Mexico-US border became notorious for its high rate of femicides. This Mexican city was then profiting from a new free trade agreement with the US, and it was no coincidence that the newly established textile and garment industry (maquila) relied on cheap female labour. This motivated many, many people to migrate to the border in search of economic opportunities.

As the maquilas were on the outskirts of the city, companies usually provided collective transport to the factories. Long shifts meant that female workers had to travel very early in the morning and late at night, increasing their vulnerability to violence. Femicides during this time involved mostly working-class girls and young women aged 11-20 years who were travelling to and from the factories, and whose bodies – when found – showed brutal displays of violence.

Since 1993 to date, there are estimates that femicides have claimed the lives of 2,300 women and girls there, although numbers vary greatly and many are likely unaccounted for. But, this is just one city in Mexico, and femicide is not a problem confined to Mexico’s northern border. It permeates the entire country. Rita Segato calls the national scale of Mexico’s growing femicide problem ‘Juarización’, referring to a process of ‘becoming like the City of Juárez.’

The most recent wave of femicides in Monterrey, as in other states of the country, not only takes the lives of adult women, but also, young adolescent girls. In the State of Mexico from 2013 to 2015 a tide of disappearances and femicides targeted mostly girls (as documented by Carrion). And data from the National Search Commission show that girls account for 55-56% of disappearances across the country.

Femicide as a public hate crime

These femicides reveal something of the scale of men’s violence against women in Mexico, as they do not only take place in the context of domestic or intimate partner violence. They all too often happen in public spaces and are perpetrated by both acquaintances and strangers. Not only is it common for women and girls who are initially reported as ‘disappeared’ or missing by their family members to be found dead, but the gendered violence inflicted upon their bodies also reflects both brutal physical and sexual violence.

Naked, tortured, dismembered and raped, female bodies can have bitten breasts, multiple traumas and mutilations that indicate something much more troubling – crimes of hatred.

The causes for the levels and intensity of femicide and gender-based violence in Mexico are complex, and more research is needed to understand the dynamics at play. However, it is clear femicides in Mexico are shaped by patriarchal gender norms and by the country’s political economy.

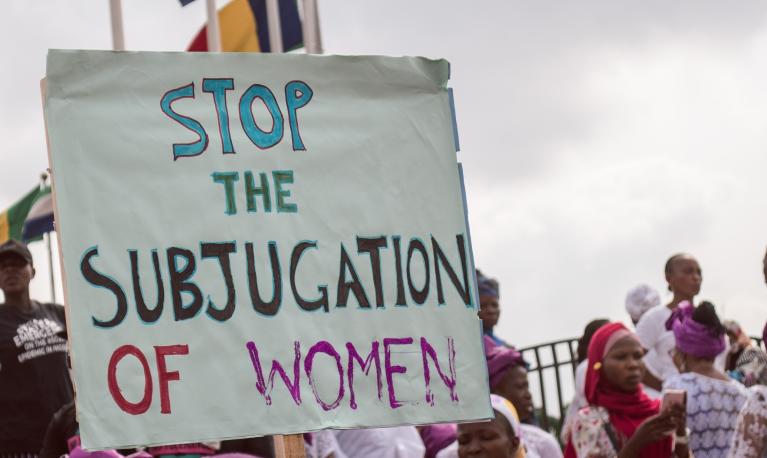

How do gender norms drive femicide in Mexico?

Worldwide, hegemonic masculinity promotes violence by coupling male identity and behaviour to dominance and control. Gender norms play a role in upholding male superiority and dominance over women and other marginalised genders. These gender norms include: male control over economic and financial resources; masculinity as linked to toughness and strength; sexist notions of honour and shame; and male camaraderie and bonding through the objectification and oppression of women.

Laura Bates and others argue that men who uphold and police stringent gender norms are more likely to perpetrate gender-based violence, particularly if, and when, the women around them fail to fulfil gendered expectation and obligations. Rita Segato has also argued that violence against women should be seen as part of a dialogue between men themselves – a process to reaffirm their masculinity in front of other men. This process reaches its maximum expression in gangs or organised crime, where violence against women has been used as a rite of passage and entry into a group.

The political economy of femicide

Femicide can be understood as a violent act against female bodies that reproduces and enforces patriarchal power and control.

Femicide has also been explained in a context of increasing inequality, which hinders a significant proportion of men from performing the social and economic responsibilities associated with hegemonic masculinity. Jacqui True argues that, as some men cannot fulfil their social roles because of increasing global inequality, they try to assert control over women to regain some sense of authority, social standing and self-esteem. Gender-based violence is inflicted due to the belief held by some men that women are to blame for the economic exclusion they face.

This view is shared by Michael Kauffman who suggests that violence against women is a mechanism men use to cope with the fear of failing to fulfil the gendered roles dictated by masculinity. Lydiette Carrion and Rita Segato point to the connections between organised crime and femicide in Mexico, as well as with the increasing militarisation of public spaces caused by the US-inspired policy of a ‘war on drugs’ declared by President Felipe Calderon.

As well as being linked to blaming women for the challenges men face, femicide is also triggered by wider political or economic factors. It can be read as a punishment for women who contest patriarchal economic and political power, and ‘displace’ men from their perceived ‘natural’ roles. It is also an act that emboldens a patriarchal form of masculinity. It is a form of communication among men – a way to (re)produce male control over what is considered to be ‘female’, and as a way to perform and establish hierarchies of masculinity in relation to other men.

Confronting the ‘fear-factory’ of femicide in Mexico

As Gqola has theorised, fear is central to this warped communication, as shown by messages spread in Monterrey through social media. These warn of criminal gangs that are dedicated to the kidnapping of women and that ask for ransoms of 10,000 pesos (around $520). Or they talk about gangs deliberately ‘hunting down’ women for up to 20,000 pesos (around $1,030) and warning them to stay at home, sending the message that women are no longer safe when they go out – not even with acquaintances.

If it is to be addressed, femicide must be understood as part of a spiralling sea of wider violence in Mexico.

It is crucial, therefore, that it is investigated through both the socio-economic and gendered dynamics of violence in the country. The latter not only speaks to gender inequality, but also to the way in which femicide is an instrument to establish and maintain patriarchal power and authority.

To speak of femicide rather than ‘crimes of passion’ speaks to the power of feminist activism over the last decades to give us the conceptual tools we need to understand these patterns of extreme violence. Moving beyond narratives of romantic passion allow the analysis to be pushed much further and to appreciate the range of reasons for why a woman’s murder may have been motivated by her gender. However, efforts to respond to crimes are hindered by Mexican institutional responses, which are plagued by rampant state incompetence, lack of political will from the men in power, and a resistance to enforce femicide protocols.

If the Mexican police and justice system continue to dismiss cases of femicide, to poorly document them, or to leave them unresolved and ignore their links to gendered motives, the analysis and data that could shed light on the causes are hindered. Identifying and unpacking institutional misogyny within spaces of power is, therefore, paramount and should be a key focus for our feminist demands and efforts.

This blog is part two of a two-part series. Read part one, Icebergs and black holes: the stories of femicide in Mexico.

About the author - Diana Jiménez Thomas Rodriguez

Diana is a PhD candidate in International Development at the University of East Anglia and the University of Copenhagen. Her doctoral research looks at the movement of No a la Mina in Esquel (Argentina) from a feminist political ecology lens. She also holds an MPhil degree in Development Studies from the University of Oxford, where she was a Weidenfeld-Hoffman Scholar. She is a co-founder of various feminist initiatives in Mexico.

Related resources

Blog

5 January 2026

Published by: ALIGN

Report

3 December 2025

Published by: ALIGN, Data-Pop Alliance

Report

28 November 2025

Published by: ALIGN, development Research and Projects Centre

Blog

14 April 2025

Published by: ALIGN

Report

5 March 2025

Published by: ALIGN

Blog

10 February 2025

Published by: ALIGN

Blog

19 December 2024

Published by: ALIGN

Blog

5 December 2024

Published by: ALIGN

Report

30 September 2024

Published by: ALIGN, Frente Nacional para la Sororidad

Report

4 September 2024

Published by: ALIGN, SISMA Mujer

Report

5 August 2024

Published by: ALIGN

Report

17 July 2024

Published by: ALIGN

- Tags:

- Gender-based violence

- Countries / Regions:

- Mexico