- Blog

- 24 November 2022

Icebergs and black holes: the stories of femicide in Mexico

- Author: Diana Jiménez Thomas Rodriguez

- Published by: ALIGN

In Mexico, my home country, 26-year-old María Fernanda Contreras disappeared on 3 April, 2022 in the city of Monterrey – the state capital of Nuevo León. She was found dead on 7 April, at a location where her mobile phone had last connected – information which had been immediately passed on to the authorities by her family.

On 9 April, another case reached the media, that of 18-year-old Debanhi Escobar. Debanhi disappeared on the outskirts of the city, and the authorities did not find her body until 11 days later. As with María Fernanda, Debanhi was found where she was last seen – in an area which authorities claimed to have searched on multiple occasions.

These two cases attracted attention to the ongoing disappearance of Yolanda Martínez who went missing in Monterrey on 31 March, just a few days before María Fernanda. Yet, Yolanda’s family were receiving little response or support from the authorities. The 26-year-old, who was last seen before leaving her house in search of a job, was found dead on 8 May. Only in the case of María Fernanda has the perpetrator of the crime been identified and prosecuted.

Now, in November, attention has shifted to a series of femicides in the country’s central region with the cases of Ariadna López, Mónica Citlalli Díaz – both of whom were found dead on the side of national highways – and Lidia Gabriela Gómez, who jumped from a taxi in Mexico City in order to prevent being kidnapped.

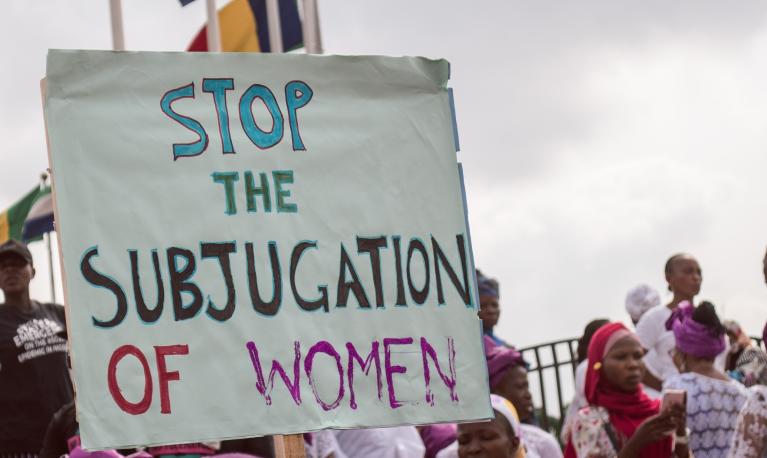

Rate of femicide in Mexico sparks feminist resistance

'Nunca más tendrán la comodidad de nuestro silencio'

(Never again will they have the comfort of our silence)

These disappearances sparked a wave of feminist protests in April and now in November – echoing the calls of the #NiUnaMenos ('not one [woman] less') movement to end men's violence against women demanded throughout Latin America. Estimates suggest around 11 women are killed by men every day in the country for gender-based motives – now recognised in Mexican law since 2012 as feminicidio (translated to either femicide/feminicide), thanks to the efforts of Mexican feminist scholars and activists. During 2020 in Nuevo León, 779 women were reported missing and in 2021, the number almost doubled with a total of 1,145 cases. In the first half of this year, from January to the beginning of May, 395 cases have been filed.

But these numbers do not represent the whole story. Two metaphors have become central when discussing rates of femicide in Mexico today: icebergs and black holes. The cases that reach the media are at best only the tip of the iceberg, as are the number of cases reported to the police. In the worst instances, there is no information at all. This reality has led Mexican journalist Lydiette Carrion to refer to the lack of available data on feminicide in Mexico as ‘a black hole’, where the scale of the phenomenon is not nearly captured in its entirety.

Intensifying waves of feminist protests denounce once again not only men’s violence towards women and other marginalised genders, but also the historically insufficient action of the Mexican state to end gender-based violence. Institutional responses are plagued by rampant state incompetence, lack of political will and even active resistance from government officials – signalling an entrenched patriarchal misogyny in Mexican institutions.

Patriarchal gender norms in the police and authorities

As the cases of María Fernanda and Debanhi show: it is not uncommon for police to find the missing girl or women somewhere previously searched on multiple occasions; for security camera feeds to be unavailable at the beginning of the investigation (often under claims that the camera was only ‘decorative’, not recording, or malfunctioning) – only to become available later in the investigation due to public pressure. It is also common for police to not call suspects in for questioning, or detain them, even in the presence of evidence. For example, for the case of María Fernanda, the primary suspect who was eventually found guilty, was called-in for questioning by the police but not detained, despite presenting evidence of scratches and bites.

Authorities also lose evidence, DNA samples take months, if not years, to come back, or autopsies which miscalculate the ages of bodies – complicating the matching of cases. It’s all too common for the police to dismiss the severity of the disappearances and discourage parents from filing a missing person report. They often allege the victim in question decided to leave – either because she ran away with a partner ‘to party and have sex’, or because she wanted to hide an unwanted pregnancy (both narratives most frequently used when cases involve adolescent girls). Sometimes police assume a victim is already dead, implying that it is ‘pointless’ to look for her.

When bodies are found, the police are often quick to argue, without enough evidence, that the cause of death is suicide or an accident due to drugs or alcohol.

In sum, Mexican authorities often fall back on gender norms to dismiss disappearances of women and girls. They appeal to patriarchal norms on female sexuality, blaming their disappearances on their ‘loose’ sexual behaviour, exonerating male violence by suggesting their deaths are their own fault, holding women responsible for the violence inflicted upon them. In the case of Debanhi, the police argued she had, tripped and fallen into a water tank in an inebriated state; in that of Yolanda, that she had committed suicide; and in the case of Ariadna, that she had died choking on food or liquids despite her body presenting bruises and scratches

In many other cases, the police actively discourage and refuse to pursue investigations claiming that ‘it is better not to lift the lid of the sewage, as one might fall through it’. They argue it is better to turn a blind eye on the problem than to face possible retaliation for investigating these cases – where organised crime, state officials, or other powerful men are suspected to be involved.

Responding to femicides through confronting institutional misogyny

Part II of this blog will discusses how the causes of femicide in Mexico are complex and not fully known. But one thing is clear: for gender-based violence to be eradicated it is essential to transform Mexico’s law enforcement and judicial institutions. Authorities have normalised violence against women and perceive women’s lives as less valuable than men’s, refusing to follow proper procedures. This is evident in that only 23% of murders of women between 2015-2021 were investigated as possible femicides.

For decades, this patriarchy within Mexican institutions has meant parents of the victims have been the ones to physically search for their daughters – patrolling the area where they were last seen, over and over again – who have led investigations, presenting clues to the authorities and compiling evidence on suspects so that the police agree to question them. This has replicated intersectional injustice, as families that have (for example) the financial means to hire private detectives, lawyers, and forensic pathologists, and to pay bribes often requested by authorities to continue investigating, are the ones that are more likely to find out what happened to their daughters.

In a country with soaring levels of impunity (less than 1% of crimes are resolved), it is thus fundamental to allocate more financial and human resources to the transformation of these institutions. Mexican authorities cannot continue to operate through entrenched misogyny, transferring the financial, time-related, and emotional costs of finding justice in the private sphere. They must recognize femicide as a public matter to be dealt with public resources. Moreover, for femicide cases to be dealt with properly by public institutions it is crucial that they are considered in relation to each other, and not in isolation. Investigating them separately ignores hypotheses, which have gained traction in recent years, of the role of organised crime and of potential human trafficking networks.

Unrelenting public pressure will be needed to address the abuse of power by state officials, to end practices of bribery which prompts officials to turn a blind eye, and to confront the power of organised networks. The task ahead is monumental and as feminists demand, transforming the criminal justice system is ever more urgent, while disappearances of women and girls continue to rise.

This blog is part one of a two-part series. Read part two, Unpacking the context of femicide in Mexico.

About the author - Diana Jiménez Thomas Rodriguez

Diana is a PhD candidate in International Development at the University of East Anglia and the University of Copenhagen. Her doctoral research looks at the movement of No a la Mina in Esquel (Argentina) from a feminist political ecology lens. She also holds an MPhil degree in Development Studies from the University of Oxford, where she was a Weidenfeld-Hoffman Scholar. She is a co-founder of various feminist initiatives in Mexico.

Related resources

Blog

5 January 2026

Published by: ALIGN

Report

3 December 2025

Published by: ALIGN, Data-Pop Alliance

Report

28 November 2025

Published by: ALIGN, development Research and Projects Centre

Blog

14 April 2025

Published by: ALIGN

Report

5 March 2025

Published by: ALIGN

Blog

10 February 2025

Published by: ALIGN

Blog

19 December 2024

Published by: ALIGN

Blog

5 December 2024

Published by: ALIGN

Report

30 September 2024

Published by: ALIGN, Frente Nacional para la Sororidad

Report

4 September 2024

Published by: ALIGN, SISMA Mujer

Report

5 August 2024

Published by: ALIGN

Report

17 July 2024

Published by: ALIGN

- Tags:

- Gender-based violence

- Countries / Regions:

- Mexico