- Case study

- 10 June 2018

What is SPRING?

SPRING is a business accelerator programme that supports fledgling enterprises to create products and services that will help adolescent girls generate income through safe sources; enjoy greater safety and well-being; remain in school and/or continue learning; and increase their savings.

Funded by DFID, USAID, and DFAT, SPRING contributes to girls' empowerment by helping businesses explore, develop and test ideas that serve girls’ needs and by providing tailored support and technical expertise to bring their products and services to market. SPRING works in East Africa (Kenya, Uganda, Rwanda, Ethiopia, Tanzania) and South and Southeast Asia (Pakistan, Nepal, Bangladesh, Myanmar).

SPRING helps businesses change discriminatory gender norms

Discriminatory gender norms are one of the main obstacles to girls’ economic empowerment. Not only do norms influence whether a business employs girls and women, they also affect how businesses reach out to them as customers or end users.

SPRING helps businesses understand the extent to which gender norms influence their operations and identify the challenges and opportunities that these norms present for their operations. Business owners participate in an intensive, two-part workshop that helps them develop insights into adolescent girls in their country.

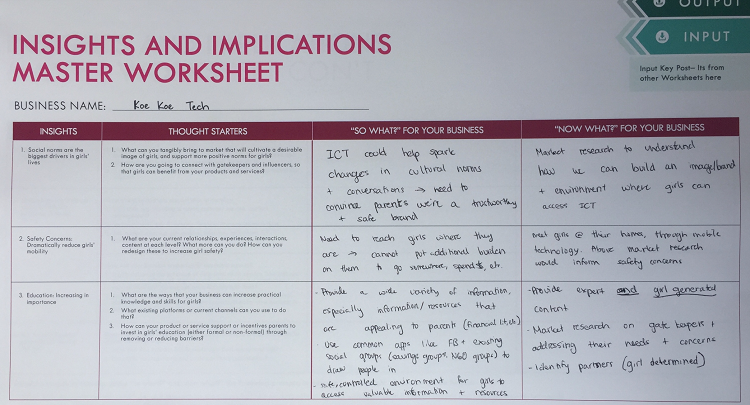

For example, the image below shows a worksheet developed by Koe Koe Tech, a business in Myanmar that provides girls with information on sexual and reproductive health using a phone application. Here, they are starting to think about how their product could contribute to shifting harmful social norms related to girls’ sexual and reproductive health knowledge and agency, and how in marketing their product they need to directly address these norms with parents.

SPRING supports businesses to either work within the framework of gender norms to provide products and services that benefit girls, or to challenge them. For example, in Pakistan, Sehat Kahani, an all-female health provider network, redesigned their clinical services to provide home based services and e-medicine to take account of girls’ and women’s limited mobility, while EdKasa, a test preparation company, addressed the issue of limited female mobility by enabling girls to learn at home and in other safe spaces though internet enabled virtual classroom platforms.

Other businesses try to tackle gender discriminatory norms by helping adolescent girls build their knowledge, skills and agency or working with parents and other stakeholders to increase recognition of girls’ needs and rights. A SPRING-supported business that has combined these approaches to challenge discrimnatory norms is Jeevan Bikas Samaj (JBS) in Nepal. JBS is a microfinance institution that established a number of girl-only savings clubs called ‘Nawa Bihani’ (‘New Morning’) in secondary schools in the Terai region. The idea for the programme grew out of a desire to empower women economically by shifting the norms that underpin lack of earnings, saving and investing opportunities before girls reach adulthood.

In providing microfinance services to women, JBS came to realise the importance of addressing norms contributing to adolescent girls dropping out of school to marry. Their strong relationships with families enabled them to work closely with girls and made the savings clubs a natural extension of their activities. They knew that for girls to be supported by their families and communities to continue their education and delay marriage, girls needed to demonstrate their ‘value’ – be it bringing a new farming skill into the household or providing the community with a service such as blood pressure testing.

SPRING’s impact

SPRING businesses monitor both the commercial viability and social impact of their products and services. While businesses vary in their capacity and motivation to collect impact data, a number of them measure individual-level outcomes such as changes in income, savings, knowledge, skills, and confidence, which are important precursors to changes in social norms.

JBS, for example, tracks the savings and school retention rate of members of its girls’ savings clubs. Early anecdotal evidence suggests that participating in the Nawa Bihani savings clubs has allowed girls to take on leadership roles in their communities for the first time (e.g. by organising health camps), to improve their own self-image, and in some cases to help convince parents to allow girls to remain in school.

While measuring broader societal changes, including changes in gender norms, is often unrealistic for early-stage enterprises, some are moving in that direction through partnerships with academic institutions or evaluation organisations. For example, Paritran, a security company in Nepal, is working with Coffey International to conduct a controlled study of their school-based self-defence training for girls. They are evaluating not only changes in girls' skills, confidence and mobility, but also changes in attitudes among parents (and school personnel) around sexual harassment of girls. Feedback from parents who attended information sessions at schools indicates that the programme has begun to shift attitudes and beliefs, which traditionally 'blame and shame' girls who have been victimised. There are also early signs of behaviour change; parents report stepping in to stop ongoing harassment. In one school, a teacher who was notorious for harassing female students over many years was finally held accountable and made to leave the school following the training.

Another SPRING enterprise, SafeBoda, a motorcycle taxi company in Uganda, partnered with Shell Foundation and Social Development Direct to conduct an impact study with female passengers. They found that women and girls reported greater mobility as a result of the service, and were choosing SafeBoda because they trusted the drivers and considered them professional, respectful, and polite to female passengers. This suggests that the company's training and support has helped to tackle the culture of harassment among drivers and potentially set a new standard for the industry.

Key lessons

1. Social norms, including gender norms, form part of the operating environment for businesses, and can affect a business’s ability to reach potential customers or to engage women and girls as employees. So apart from a business’s social motivations, there may be a commercial case for shifting discriminatory norms. SPRING has already seen that increases in knowledge, and attitudinal and behavioural changes enable businesses to introduce new products to the market, and expand their existing customer base.

2. Identifying relevant gender norms that affect specific populations in a specific context through qualitative research with users is a key element of a human-centered design process. It helps business develop effective products and services, whether this involves tackling discriminatory norms directly or working around them. Reflecting the diverse contexts in which it works, and the variation in gender norms, SPRING’s support to businesses to engage with social norms has needed to be very individualized in order to be successful. For example, working around norms related to sexual and reproductive health in poor and highly conservative rural areas of Pakistan, but tackling norms related to mobility more head on in better off urban areas of Kathmandu.

3. Being aligned with the core business is key. Pulling businesses too far out of their comfort zones, asking them to pivot significantly in order to address gender norms, is unsustainable and ineffective. For example, SPRING has found that asking businesses to provide employment opportunities for girls or women in non-traditional roles (such as having girls as marketers/sales agents for a water business in Bangladesh) can backfire, as it can end up creating more work for the business (incurring greater cost with limited payoff). It is important to take a longer term perspective, seeing businesses and their contribution to social change in broader context.

About the authors:

Emily Waters is an M&E Advisor for the SPRING Accelerator, where she helps to capture programme results and works with social enterprises to conceptualise and demonstrate their impact on adolescent girls. Before SPRING, she spent the previous 10 years managing research studies and creating M&E systems for development and health programmes in Zambia and the United States. She has an MPH from University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Rebecca Calder has a Ph.D in social anthropology and 25 years of policy and field experience in Asia, Africa, and the Pacific as an independent consultant, researcher, trainer and adviser. Rebecca is a thought leader and expert in the sphere of adolescent girls' economic empowerment and social norms. She has worked on social development and social policy issues with: partner governments; the World Bank and the Asian Development Bank; a wide range of UN agencies; bilateral agencies; international, national and local civil society organisations; and the private sector.

- Countries / Regions:

- Africa, South-East Asia

Briefing paper

10 January 2026

Briefing paper

10 January 2026

Blog

5 January 2026