- Toolkit

- 20 March 2019

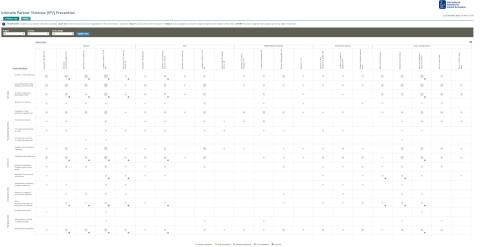

Intimate partner violence prevention evidence gap map

- Author: ESubden

- Published by: International Initiative for Impact Evaluation

This evidence gap map shows where evidence exists on different types of interventions to tackle intimate partner violence. While it does not use the term ‘norms’, many of the approaches covered have been used to shift norms that condone intimate partner violence.

About the tool

Since the first map was published in 2017, the evidence base has expanded significantly. This update covers evidence published between August 2016 and July 2018. The map comprises of 95 completed and 44 ongoing impact evaluations and 2 systematic review protocols, totalling 141 studies. The authors used the same outcomes and interventions framework as the original map.

Main findings:

- Most of the evidence from low- and middle-income countries is concentrated in South Africa, India, Uganda, Bangladesh, Tanzania and Mexico.

- Thirty-five per cent of studies disaggregate results by sex in their analyses and 28 per cent analyse power relations or gender norms as an outcome.

- Thirty-four completed impact evaluations focus on a vulnerable subset of the population, including refugees, pregnant women and sex workers.

- Two previously empty areas of the map now have evidence – communication campaigns for institutions, and socio-economic triggers as outcomes for men, often measured by changes in behaviour, knowledge or attitudes towards IPV.

- Twenty-six newly reported ongoing impact evaluations show that the evidence base will continue growing.

Implications for policy, programming, research investments:

- Impact evaluation researchers should measure more male outcomes; measure changed gendered social norms as an outcome; and include vulnerable populations, such as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer partners, in the sample.

- Researchers should synthesise the existing evidence on the impact of income-generation programmes, such as cash transfer or asset transfer programmes, on women’s experience of or response to IPV.

- Implementing organisations will benefit from forging stronger relationships with local governments, educational systems, and community-based organisations to enable impact evaluations that evaluate IPV prevention interventions for the populations they serve.

- Organisations funding research need to direct more funding and give strategic priority to multi-arm randomised evaluations and randomised controlled trials, designed with the improvements recommended above, and require their grantees to conduct long-term follow-up surveys and cost-effectiveness analyses.

- All research needs to disaggregate by sex.

- Countries / Regions:

- Global

Related resources

Case study

1 April 2024

Case study

9 June 2021

Report

10 May 2021