- Blog

- 24 Noviembre 2023

How does artivism contribute to ending gender-based violence?

- Author: Diana Jiménez Thomas Rodriguez

- Published by: ALIGN

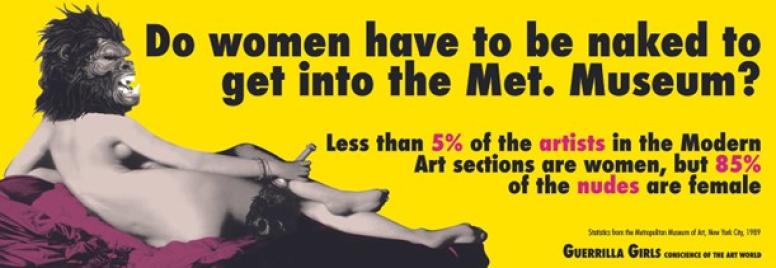

Feminist art is everywhere: we find it in music, in theatre, in performance art, in the visual arts, in film, and in crafts. Feminism broke into the art world to challenge the prevailing biases that shape what we see as art, and who we see as an artist, and to strengthen the connection between arts and the struggle for social justice.

Not only has art been central to feminist movements – for example, poster art and cartooning have been part of the UK feminist movement for decades – but feminism has also played an active role in re-conceptualising art itself as a form of activism.

It has generated new artistic forms, such as new genre public art and useful art. And it has revitalised the connection between art and social change, present in movements such as dadaism, the Casablanca School, the situationist international, social realism and stridentism.

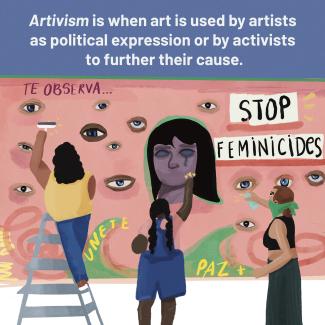

Artivism is a term that captures the relationship between art and activism. It refers to artists who use their art intentionally as a form of political engagement and work, as well as to activists who use art as part of their collective action to further their cause.

Feminist artivism, therefore, includes the work of artists like Guatemalan rapper Rebeca Lane and Mexican Zapotecan artist Mare Lirika who sing about gender roles, femicide and body autonomy (among other issues). Feminist movements also make use of the creative arts, such as the performance by Chile’s Las Tesis, Un Violador en tu Camino (‘A rapist in your path’), which has featured in protests against gender-based violence (GBV) worldwide.

GBV has been a prominent focus for feminist artivism. This preoccupation reflects the entrenched prevalence of GBV worldwide (in both the private and public sphere), and its function as a mechanism to perpetuate gender inequality and oppression.

How can feminist artivism tackle gender-based violence?

Art can appeal emotionally to us and evoke strong feelings. By mobilising our emotions, feminist artivism can create an affective ‘stickiness’ that supports gender norm change.

Feminist artivism can pose a direct challenge to the discriminatory gender norms – that is, the implicit and informal rules that inform and guide gender roles and relations – that underpin GBV. Art is an effective way to challenge our normalised beliefs, attitudes and behaviours, as it can shed light on their inconsistencies, omissions, and biases. Art installations showing the clothes that victims-survivors of GBV wore at the time they were assaulted have been used, for example, by feminist movements and collectives, such as Ropa Sucia (Mexico), Chega de Fiu Fiu (Brazil), and #Donttellmehowtodress (Thailand), to disrupt and contest victim-blaming by dispelling the belief that women provoke their aggressors through their dress.

Feminist artivism is also well-placed to promote new gender-equitable norms. Art is a tool that allows us to explore new narratives (meanings, values, ideals, and norms), and to articulate and communicate these to others. In 2022, for example, the Mexican organisation GENDES partnered with the theatre company Vereda Teatro to host the play Danny y las Tiasaurias for a year. The play explores the connection between emotional suppression and GBV, promoting gender-equitable and emotionally healthy masculinities among boys. Similarly, La Otra, a Spanish singer, articulates and communicates new narratives for violence-free relationships through pieces such as Contigo (‘With You’).

Below we highlight four other ways in which feminist artivism can support gender norm change around GBV:

First, it can make GBV more visible

Many artists and feminist collectives have used art to contest the invisibility of GBV, which remains ignored and unaddressed by states and by societies at large. For example, the installation by Mexican artist Elina Chauvet, Zapatos Rojos (Red Shoes), active since 2009, places 100 pairs of donated red shoes in public spaces to represent victims of GBV and women who are missing. Similarly, the installation by Canadian Métis artist Jaime Black, The REDress project, is a visual reminder of the more than 1,000 missing and murdered indigenous women in Canada. Artivism, can, therefore, be a powerful way to denounce and raise awareness about GBV.

By making GBV visible, feminist artivism can symbolically re-appropriate and re-signify public space. Art installations and street art, for example, can be a way to occupy public space – an assertion of women’s rights.

Second, it can make feminist ideas accessible and engaging

Artivism communicates and disseminates feminist ideas, theories, and proposals verbally and non-verbally. The performance by Las Tesis, for example, aimed not only to denounce GBV, but also to communicate different feminist theories on GBV to a wider audience. Art is also useful in exploring and communicating the complexity of issues, as it can raise questions (rather than always providing answers) and bring in multiple perspectives. Artivism can be a way to share knowledge and/or to educate about GBV.

Third, it can support movement building

Art brings people together, nurtures positive relations and strengthens group identity. It can and does support and strengthen feminist movements or collectives working to end GBV. Mandolini argues that the group Lucha y Siesta has used art – through its Luchadoras (Fighters) campaign – to motivate people to join movements and take up feminist activism.

She also notes that Una di Meno’s use of graphic art in its campaign against obstetric violence – Matrioske parlanti contro la violenza ostetrica – encouraged and nurtured diversity within the movement through visual representation. Artivism – like Vivir Quintana’s piece Canción sin Miedo (‘Song without fear’) – can support movement-building by mobilising people to take action through its affective stickiness.

Fourth, it can support victims-survivors of GBV

Art is a medium for the recognition of victims-survivors, and a way to build and communicate solidarity to and between them. This was the aim, for example, of the installation Be my Face, held at the Hotel Grand Prishtina (Kosovo), which was the site of conflict-related sexual violence in the 1990s. It is also a tool to provide psychological and emotional support to victims-survivors, helping people to explore and express their feelings – particularly those that are difficult or painful. Through this therapeutic dimension, artivism can support the psychological well-being of victims-survivors of GBV.

Feminist artivism against GBV is and can be powerful. It can directly contest the harmful gender norms that underpin GBV and promote new ones. It can also support gender norm change indirectly through its impact, for example, on movement building and the dissemination of feminist ideas.

In addition, feminist artivism expands people’s avenues for political expression and engagement, and has wide-ranging impacts. It offers a way to pursue political action that is collective as well as individual. It promotes change among those who make it and those who see it, and in the case of participatory art – which engages community members and audience members as participants, such as interactive theatre – on those who facilitate and participate in it.

Yet, feminist artivism can, and has, put artivists themselves in danger of backlash and GBV. Hossna Hanafy, Farida Batool and Claudia Michaus, for example, have received numerous threats because of their artivism, and Las Tesis faced charges in 2020 for inciting violence against the police. It is crucial, therefore, not only to recognise the work and the risks faced by feminist artivists worldwide, but also to accompany them and echo their call to eliminate GBV once and for all, in both the arts and conventional political action.

To find out more about feminist artivism, please see The Art of Feminism, Feminist Art Activisms and Artivisms. Stay tuned for more ALIGN publications on this topic in 2024.

Tweet this blog

How does artivism contribute to ending gender-based violence? New blog by @ALIGN_gender.

#gendernorms #ENDviolence #16days #feministartivism

About the author

Diana Jiménez Thomas R. is a Senior Research Officer at the Gender Equality and Social Inclusion team at ODI. She focuses on social movements – particularly feminist and environmental movements. She works on a number of projects at ODI, including ALIGN, that relate to feminist activism, gender-based violence, and gender norm transformation.

- Countries / Regions:

- Global

Related resources

Blog

5 Enero 2026

Published by: ALIGN

Report

3 Diciembre 2025

Published by: ALIGN, Data-Pop Alliance

Report

28 Noviembre 2025

Published by: ALIGN, development Research and Projects Centre

Report

4 Noviembre 2025

Published by: Breakthrough, Equality Now

Report

20 Octubre 2025

Published by: ODI Global

Report

22 Septiembre 2025

Published by: ODI Global

Report

16 Septiembre 2025

Published by: UN Women

Report

21 Agosto 2025

Published by: ODI Global, CIEDUR

Blog

14 Abril 2025

Published by: ALIGN

Report

5 Marzo 2025

Published by: ALIGN

Blog

10 Febrero 2025

Published by: ALIGN

Blog

19 Diciembre 2024

Published by: ALIGN