- Blog

- 19 February 2019

The ‘Why’ and ‘How’ of sustaining work on changing gender norms

- Author: Hemlata Verma

- Published by: ALIGN

Unlike a news story with a short shelf life, research on changing gender norms must look beyond project sites and timelines towards longer-term sustainability. And institutionalisation is one key pathway. This reflection widened my quest to seek and create information as I made the leap from working as a journalist to become a researcher on gender inequality.

For nearly five years, I have been conducting research at the International Center for Research on Women (ICRW) to design interventions that use a gender transformative approach with adolescents to change unequal gender norms and accompanying attitudes and behaviours. This approach expands their agency by engaging them in critical self-reflection on the unequal gender norms that affect them, enabling them to use their personal convictions and new knowledge to challenge the status-quo.

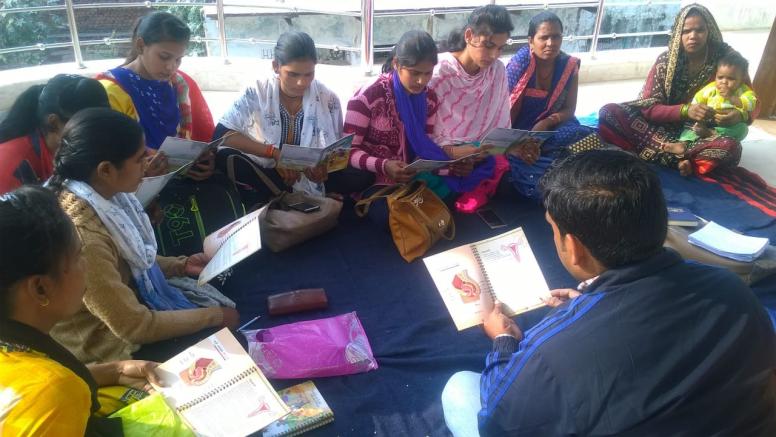

session using the PAnKH Diary, in Gujjra

Khurd village of Dholpur district in

Rajasthan, India. © ICRW

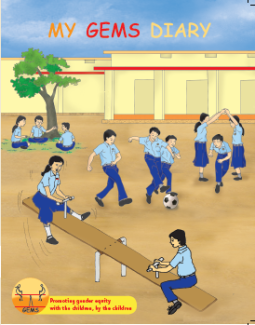

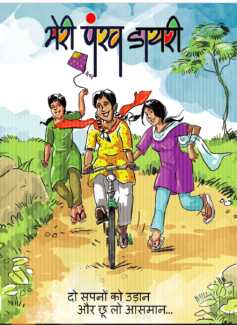

I began with the Gender Equity Movement in Schools (GEMS), which aimed to prevent gender-based violence (GBV) among adolescents studying in grade VI-VIII in coeducational government schools in Jharkhand state in India. Next, I designed the Promoting Adolescents’ Engagement Knowledge and Health (PAnKH) programme to improve sexual reproductive health (SRH) among 12-19-year-old adolescent girls in a community setting.

Both programmes co-created knowledge and conversations with the adolescents and ensured safe spaces for them to use their new skills. Importantly, both programmes created tools to keep the conversations going long after the programmes themselves had come to an end.

They created two ‘workbooks’ – ‘My GEMS Diary’ and ‘My PAnKH Diary’, full of information, lively comic strips, discussion questions, games, quizzes and space for written reflection. The aim was to create tools that students could use to sustain their messages and knowledge into the future. Participants could also use the workbooks to trigger new conversations with families and peer-group networks.

How participants used the workbooks

Equity Movement in Schools,

program. © ICRW

The GEMS Diary and PAnKH Diary received by adolescents (boys and girls in the GEMS programme and adolescent girls only in the PAnKH programme) was, for most – if not all – their first-ever personal diary. This gave them a chance to write down thoughts about their own identity, dreams, strengths, likes, dislikes, gendered experiences of growing up and their quest for change. In this, they built on the agency of adolescents.

Both workbooks have age-appropriate content on themes already covered in the group education activities. And while both diaries focus on aspects of bodily integrity and body changes around puberty, the PAnKH Diary looks at these issues in more detail, with an emphasis on the human reproductive system, including diagrams and images, as well as menstrual health. The PAnKH Diary also has a hand-out of information on contraception, fertilisation, pregnancy and ante-natal care.

Adolescent girls and boys who received the GEMS Diary found it much easier to use this tool to start a conversation on gender norm change with their families than the adolescent girls who took part in the community-based PAnKH programme. This was because the GEMS programme ran in government schools, with institutional support for its work from the word go.

When norm change was steered from within the formal education system through trained teachers and then through the GEMS Diary, students felt a greater willingness to carry these messages home. Their parents and siblings were also convinced and confident, as these messages were coming from the education system – one of the most trusted institutions – and were backed by the teachers, whom everyone respects. The Diary was widely shared by students with their relatives and peers. Many students would carry it in their school bags each day and could be seen using it to play games with their peers.

during a session on GEMS Diary. © ICRW

Under the PAnKH programme, one adolescent girl who had dropped out of school after grade V, shared her feelings about the diary, saying, ‘girls who go to school have their own school bag, note books, school dress, pencil box, school shoes, etc., but I don’t have any of this. This diary is my first personal asset.’

Given the social taboos that force girls to be silent on SRH, the information on this issue in the PAnKH Diary was the most popular among adolescent girls, whether they were married or not, and led to many conversations in girls’ groups. However, the content on SRH also made girls hesitant to take the diary home. And those who took it, kept it hidden from the men in their families. They feared a backlash, as girls are not expected to talk openly about their body, menstruation or reproduction.

Most girls personalised their dairies by writing their own names in them. But once the group education session was over, they handed it back to the village mentor for safe-keeping, hoping that they would be able to take it home someday. Many mentors asked them: ‘The biology book in the school also has the same graphic presentation of the reproductive system. When you have no hesitation in taking that home, then why not the PAnKH Diary?’

The girls answered that the biology book came from the government education system, and their families would not question them over it. But the PAnKH Diary was given to them as part of a programme run by a community development organisation. It was led by female community mentors who, unlike school teachers, were yet not accepted or recognised in the community or by the formal education and health systems as subject experts.

Strategies to institutionalise the workbooks

Recognising the strong need to institutionalise the workbooks through community-based platforms, we adopted three strategies under the PAnKH programme:

- Introducing the PAnKH Diary workbook in self-help group (SHG) meetings: Adolescent girls said that conversations on these issues could begin in families if their mothers were comfortable with this. Therefore, the programme’s community mentors are now using the PAnKH Diary to discuss SRH with women in the monthly meetings of the village organisation (VO) – a village level federation of the SHGs. This has helped to introduce women to the idea of challenging gender norms on silence, shame and taboo around SRH. ‘Even as they giggle away initially while understanding the reproductive system through the pictorial depictions, exposing them and making them used to seeing and talking about such information will pave way for comfort on talking on SRH in the long run’ says Seema, a community facilitator.

- Introducing the Diary to village-level female health workers: The ASHA (Accredited Social Health Activist) is mandated under the national health mission and the national adolescent health programme – Rashtriya Kishore Swasthya Karyakram (RKSK) – to engage with adolescent girls and boys on SRH. However, training for ASHAs on this issue has yet to happen in most parts of the country. We leveraged the RKSK mandate to introduce the diaries to ASHAs in programme villages, so that they can use them as reference materials to talk to girls. The presence of the PAnKH Diary in the health centre will also make it easier for anyone in the village to read it, become comfortable with it and use it to seek correct information.

- Conducting group sessions with girls using the Diary: After two years of the programme, school children had started to use the GEMS Diary on their own. Because it was not possible for girls to the PAnKH Diary at home, we had to create specific sessions under the programme to give space for girls to do the activities.

My two key take-aways for practitioners who are working to sustain the process of gender norm change beyond a programme’s duration and sites are: endorse workbooks through the institutional platforms that are already in place, and create dedicated spaces in the community where girls, in particular, can use these tools.

About the author

Hemlata Verma is a Technical Specialist in Gender, Violence and Sexual Reproductive Health Rights.

Hemlata Verma is a Technical Specialist in Gender, Violence and Sexual Reproductive Health Rights.

She brings on board an amalgamation of expertise in communication and social development. At ICRW, she handles operations research, program evaluation, gender analysis and capacity building. She has been engaged in designing research and interventions with adolescents on primary prevention of gender-based violence (GBV) and violence against women and girls (VAWG), as well as on sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR).

- Countries / Regions:

- India

Blog

8 January 2024

Case study

15 September 2023

Blog

23 August 2023